Our Routes to Our Forgotten Roots

How working with farmers in rural Myanmar led me back to lost parts of my Scottish culture

I am sitting around a table on a cold and rainy Edinburgh day. One woman has brought a book about native tree species. We are going to learn the name of one today.

Beech.

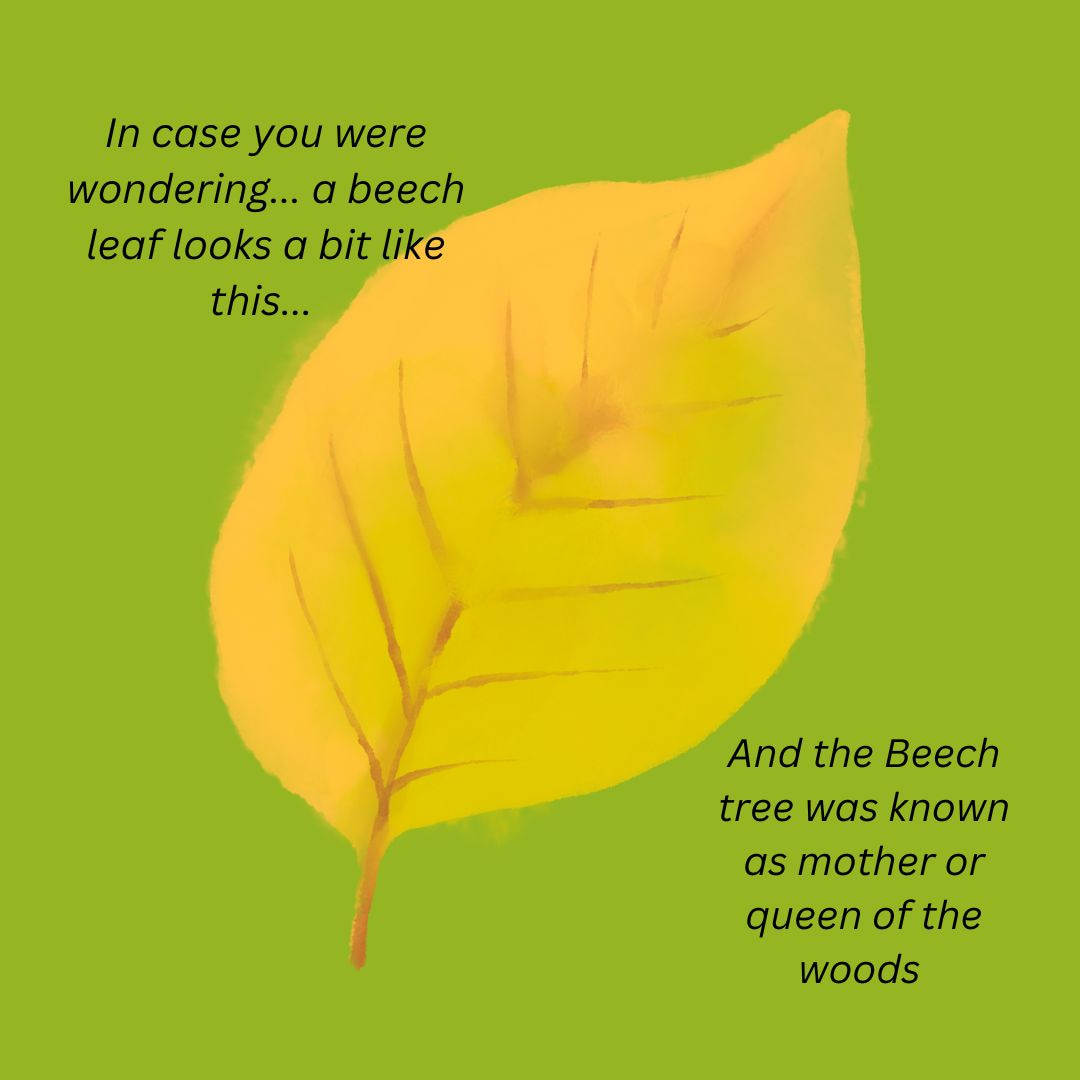

She reads from the book, we look at a picture of the shape of its leaf, read its traditional uses. We discuss any memories and associations we have about Beech. We go out into the garden and try to identify Beech. We think we find one, but we are not sure.

It is awkward, it is clunky but there is something about this process which also feels essential.

A few years before this, I sat with groups of women farmers in Myanmar, who told me about their lives for research projects. They told me about the plants around them and their uses. They told me about their local landscape and the different and detailed ways in which it had recently changed.

As I listened, I remember realising that I did not know details about the Scottish landscapes I grew up in the way these women knew. I knew street corners and shops and even pavement cracks but not the details of local wildlife.

I remember noticing how the knowledge of Burmese women farmers was devalued by themselves and others in their society. I remember noticing how this knowledge is also devalued by global systems as a whole.

I sometimes wonder when it was that my ancestors lost their knowing of the natural world. I know that my great-great-grandparents moved into the city of Glasgow from parts of rural Scotland and started up businesses in things like milk delivery.

I imagine it was sometime around then. Traditions built into daily life, practical knowing, started to lose their value. I remember my parents had a book of flowers, to recognise the names of the local wildlife. I remember when I was younger, this identification of the natural world felt pedantic and unnecessary.

When I began working with Indigenous and rural communities, like the women in Myanmar, I used to think that they had sacred knowledge which had nothing to do with me. A culture to be respected - but not touched.

Yet, as I became friends with these people, the more I saw the way their cultures moved and evolved - they were not static. And I started to see glimpses of my home culture in their stories. Hazy, but connected. Lost, while many in Myanmar were not yet lost.

And since I have noticed so many small connections between those cultures and mine.

For example, Historian William Halliday wrote:

“The evil spirits in the forests of Burma find running water as difficult to cross as do the witches of Scotland.”

Michael Newton’s careful research of Gaelic writing documents the close relationship Gaelic communities had with their landscapes. He shares quotes, which are almost word for word, identical to the words shared with me by Indigenous women I worked with in Myanmar.

I did not inherit this knowledge of the natural world. Many people did not. Yet if we have lost what was once ours, it must also be possible to refind it.

In Scotland, nature became a technical domain but for women farmers in Myanmar, it was not. They showed me that the way to relearn nature is not through repeating the patterns of the systems which disconnected us in the first place. Heritage is not found in science or research. It is not in the right terminology, or acquired expertise and not through ownership and dominion. It is in seeking to understand our world through friendship and a willingness to be touched by the lessons that nature herself will teach us.

Instead of thinking these skills are only for those who inherited them, befriending the natural world requires clumsy attempts at getting to know the nature in our neighbourhoods.

That might mean stumbling because we have no one to teach us.

That might mean paying attention and that might mean speaking out so that our inheritance is not taken from us again.

It is our world. It roots us, it grounds us.

It also contains many of the answers we need to heal the systems which have harmed our climate. The same systems which caused us to devalue and commodify nature and in doing so, discredit the cultures which connect our human lives to the bigger living systems which hold us and keep us alive.

A moment to mention the conflict in Myanmar

In sharing this piece, I want to take a moment to highlight the under-reported conflict in Myanmar and draw attention to the many Myanmar citizens taking daily risks for their political freedom.

Studies show Myanmar to be the country facing the highest level of conflict worldwide (and the second deadliest - after Ukraine).

Since the coup d’etat in 2021, over 50,000 people have lost their lives and over 20,000 people have been imprisoned for their political beliefs.

I also think it is important to bear in mind, the impact that British colonial occupation had on Myanmar and the way that history plays out in Myanmar today. Or in other words - it might be happening over there - but the suffering, in what can seem a very distant country, is linked in many ways to our lives and our history.

That is not to cast blame, but to remember, that we live in a connected but also unequal world, due to these past legacies.

Some Myanmar resources

If you want to find out more about what is happening in the country:

This is a good top-level summary.

You could follow these Instagram updates on an account which was started around the time of the coup d’etat and still posts regularly: Listen Up.

You could read these independent news sites from Myanmar: The Irrawaddy and Myanmar Now

For example, this piece on the role of global capitalism in creating the current political crisis.

There are also a lot of good books which help to understand the country, its rich ethnic cultures, religious stories, as well as its unique history. I will share those recommendations another day.

I hope this article gave you a new idea or learning. If it did - and you feel inspired - please do share this with your community.

Or if that’s not your thing. Leave a comment and tell me something about the nature in your backyard.