A month before I arrived in Yangon, the cars came. Descending on the city from China and Japan, blocking the two-lane roads with endless traffic jams.

It used to be so peaceful, people would tell me.

It was no longer.

Living in Myanmar I used to feel like I was trying to piece together old stories, to capture the essence of a place which had existed more authentically - just before I had come along to witness it.

I would walk the streets of Yangon, trying to see through the crumbling colonial and military structures. Attempting to glimpse a mythical country that had left only traces of itself behind.

The arrival of the mixologists

And in the years I lived there, I also saw the city change. The old Myanmar became the new.

Coffee shops appeared without warning on my street.

A bridge would slowly emerge ahead of me on a previously flat road.

Shopping malls, Mexican restaurants and mixologists all found their way into the life of the city.

And there was the constant sound of construction: new condos labelled ‘2012’, towering over colonial houses, abandoned offices and military structures. The new buildings - rectangular and stream-lined. The old ones - covered with chipping paint and dripping with plants.

I realised these books had survived independence, a coup d’état and military rule to lie on the pavement in a dusty, uncertain democracy.

Finding a secret Myanmar between pages

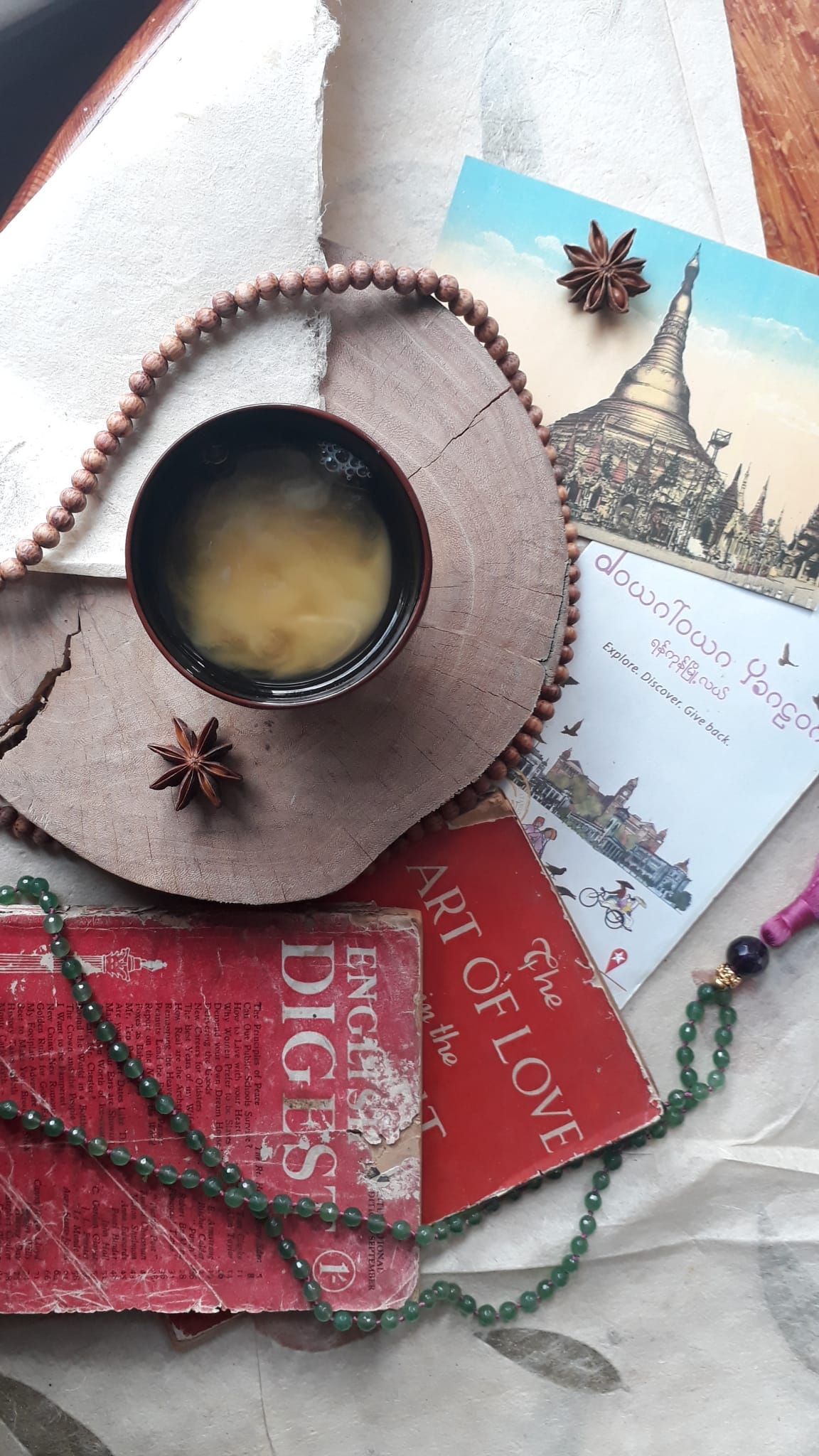

As I wandered the city, I would often stop at stalls where books piled high on tarpaulins. They had a mystical paper smell which seemed to hold those stories of the past that I could not find in the country itself.

The booksellers would throw their English-language books in my direction, one by one. A learner’s guide to English with banal essays and vocabulary lists, covered with a student's scrawl. Novels about British and American people doing brave things in dangerous places.

The soft thud of more books at my feet. I would look at them all, hoping they might tell me about the secret Myanmar I had heard so much about.

One book told a jaunty tale of British travel in Africa. 'A whale of an adventure' the back cover exclaimed. The date of publication was 1952, just after the Burmese gained independence from British Colonial rule. Another 1950s American book on personal development instructed readers 'How to be more enthusiastic'.

'Enthusiastic people succeed' the author claimed. I wondered if the bookseller would agree.

I wondered if any of the writers ever imagined that their words would make a living for a man on a Burmese roadside almost 100 years later, or that their essays would be read again in the twenty-first century.

I realised these books had survived independence, a coup d’état and military rule to lie on the pavement in a dusty, uncertain democracy.

Who read these? I wondered. Their paper marked by insects’ teeth, their pages leaving dark yellow stains on my fingers, their spines carrying the heavy scent of the past.

Perhaps, a man travelling to India at the end of the colonial era. Did a young girl desperate to learn English devour their dusty pages, nothing else to read?

Or did an impressionable boy sit at a teashop to wonder at the British people, so different from the Burmese? Did these books go to the border forest areas and small towns where it is difficult to travel? Or did they amble from tea shop to restaurant in Yangon?

If the books could speak, I imagined their stories would be more interesting than the words still on their pages.

I like how these stories illustrate the tiny moments of our past, the day-to-day thoughts and outdated ideas - which get lost in the broad brush of history.

Because over 10 years, Myanmar changed quickly. From a country cut off from the world to one inhabited by foreign companies, NGOs. Young people and new organisations developed creative new ways of seeing the future. So many tiny details of change were built into the streets before me.

Then a coup d’etat in 2021 brought further political change. And those dreams for a different future scattered.

People are often afraid of freedom

Of the books from Yangon, my favourite find was 'The English Digest’, dating from the early 1950s. It contains essays on varied topics, from the then-new UN Charter to lifestyle stories.

One woman, naming herself the 'Impatient Spinster', writes that she is desperate to return to America from the United Kingdom, as Scottish men are afraid of courting a girl, even jumping 'on a bus going in the opposite direction' when they see her. Other essays instruct 'Never Trust a Lady'; describe 'The Best Years of My Wife' and offer 'Beer to Make Your Breeches Stick'. They paint a picture of Britain when it left Burma in 1948.

The last essay in the ‘The English Digest’ is by a man called Alan Taylor who writes: ‘Why Women Prefer to be Slaves'.

He argues that men should make the family breakfast, claiming that 'equality has to begin at home'. A matter, he says, Lenin also knew well, as he too shared the housework with his wife.

He boldly continues: '(m)ost women would rather cook the breakfast. The reason is simple. They don't want to be equal. This is not surprising,’ he states '(p)eople are often afraid of freedom.’

His words echoed curiously into the Myanmar of 2012 and even more strangely today. I wonder if this is something that dictators tell themselves in the full strength of their oppression, to justify their meticulous control.

I wonder if this is something the people of Myanmar consider; if it crossed the mind of political prisoners or the people’s armies. I wonder if Taylor would think that they were afraid of freedom too?

One thing that was clear from watching the 2021 coup d’etat unfold, is that however that moment will be spun by history, it was very much about the fears and desires of the powerful. Everyone else was left to navigate the consequences.

At the end of the essay, Taylor recommends: '(a)ll the same, try freedom. It means a lot of trouble but it is worth it in the end.’

Words which seem part of a strange revolutionary manual that survived decades of military print censorship, hidden in this inconspicuous book on British life.

They are also words which encapsulate the lives of many Burmese people, who for more than seventy years, keep trying freedom, certain they will like it. While the legacies of colonialism and military government show that the way political freedom is decided often has very little to do with effort.

Conversation Starter

If one of your essays were to survive for fifty years and re-appear on a roadside stall - which one would you choose?

Thank you for reading Notes from Saving the World.

This is a place to share experiences that our inner journeys to outer journeys and our transformations to bigger global change.

I write about the systems we live in through the lens of my personal and professional experiences of twenty years working in the aid sector.

I hope my stories might help connect your lived experiences to our global narrative. And ultimately - feel a bit less alone.

A moment to mention the conflict in Myanmar

In sharing this piece, I want to take a moment to highlight the under-reported conflict in Myanmar and draw attention to the many Myanmar citizens taking daily risks for their political freedom.

Studies show Myanmar to be the country facing the highest level of conflict worldwide (and the second deadliest - after Ukraine).

Since the coup d’etat in 2021, over 50,000 people have lost their lives and over 20,000 people have been imprisoned for their political beliefs.

This also has wider impacts on the economic situation in the country - for people like the booksellers mentioned in this story.

It is also valuable to remember the impact that British colonial occupation had on Myanmar and the way that history plays out in Myanmar today. Or in other words - it might be happening over there - but the suffering, in what can seem a very distant country - is linked in many ways to our lives and our history.

That is not to cast blame, but to remember, that we live in a connected but also unequal world, impacted by these past legacies.

Some Myanmar resources

If you want to find out more about what is happening in the country:

This is a good top-level summary.

You could follow these Instagram updates on an account which was started around the time of the coup d’etat and still posts regularly: Listen Up.

You could read these independent news sites from Myanmar: The Irrawaddy and Myanmar Now

For example, this piece on the role of global capitalism in creating the current political crisis.

There are also a lot of good books which help to understand the country, its rich ethnic cultures, religious stories, as well as its unique history. I will share those recommendations another day.

If you liked this, you might also like this:

Catriona- Thanks for sharing this. One thing I always find from traveling to southeast Asia is the surprising self-discovery I always get at the end of it. It's like it deepen my knowledge of the self, particularly what's important for me (that I wasn't even aware I value, like the deep sense of respect to others) and what I 'thought' was important (that turns out isn't all that important, after all). And for some reason, living in the US now, I can't really see this in a palpable way unless I travel halfway around the world. Perhaps it's because humans learn so much by way of contrast and heightened sensibility. Either way, this is a great reminder. :)