Ways Grammar Books Led Me to Belong to Myself

Languages are like affirmations, you say the words over and over again until you become connected to nations.

French

I first learned a foreign language when I turned 12 - a requirement of the Scottish school system - and as French was the only one available at my school, that is the language I studied.

I liked French. My brain found memorising verbs and vocabulary easy. And in a Glasgow school where I was friendless and relentlessly bullied, I liked reading about Jean Claude et Marie Claire jouent au tennis. Because I thought perhaps they would be my friends.

French opened in me the idea that there might be other people out in the world who were like me. French wasn’t just lots of vocabulary and irregular verbs. It was a survival mechanism against loneliness.

Of course, when I finally went to France, they weren’t there on the tennis courts waiting.

There was a huge cultural adjustment to navigate. And I did.

Yet, instead of finding my people, I found other ways of being a person. Integrating them into me. Learning there were more ways to be cool than those school bullies maintained.

Spanish

I learned Spanish because it looked easy. Broadly similar to French (which I now had a university degree in), and because I had worked out, I probably needed a trio of global languages to get an international job.

I was right on both counts. The French grammar provided a toolkit to navigate Spanish. And that Spanish helped me get my first international development job in Nicaragua, vastly improving over my two years talking to office colleagues and coffee farmers.

Even though my time in Nicaragua was often hard, Spanish was a language I learned to laugh in. My accent became suave/soft. Central American Spanish with a vos sos, not a tu eres. An accent which reminded me of home.

Italian

I learned Italian because I moved to Italy to be with my then-partner. I read a grammar book, and within two weeks I understood his friends.

He said I spoke Italian like a Spanish hooker. I was ok with that.

The grammar was French. The vocabulary Spanish. I blended them together and did grammar exercises in a small notebook until I got the hang of Italian’s ways.

I didn’t need it to be perfect, I enjoyed going out for aperitivo or cornetto integrale and hearing people talk about things, understanding them and not being left out.

Arabic

I learned Arabic for love and then also healing from love, because my ex was also Egyptian, and I didn’t like not knowing his native tongue.

I first studied the curved letters of classical Arabic in a classroom in London, excitedly recounting to him what I had learned.

After we broke up, I moved to Egypt and learned the local Ameya dialect. I found it easy to memorise. But equally easy to forget.

I wish I could say the same about our relationship. I was repairing his wounds long after I forgot his language.

Burmese

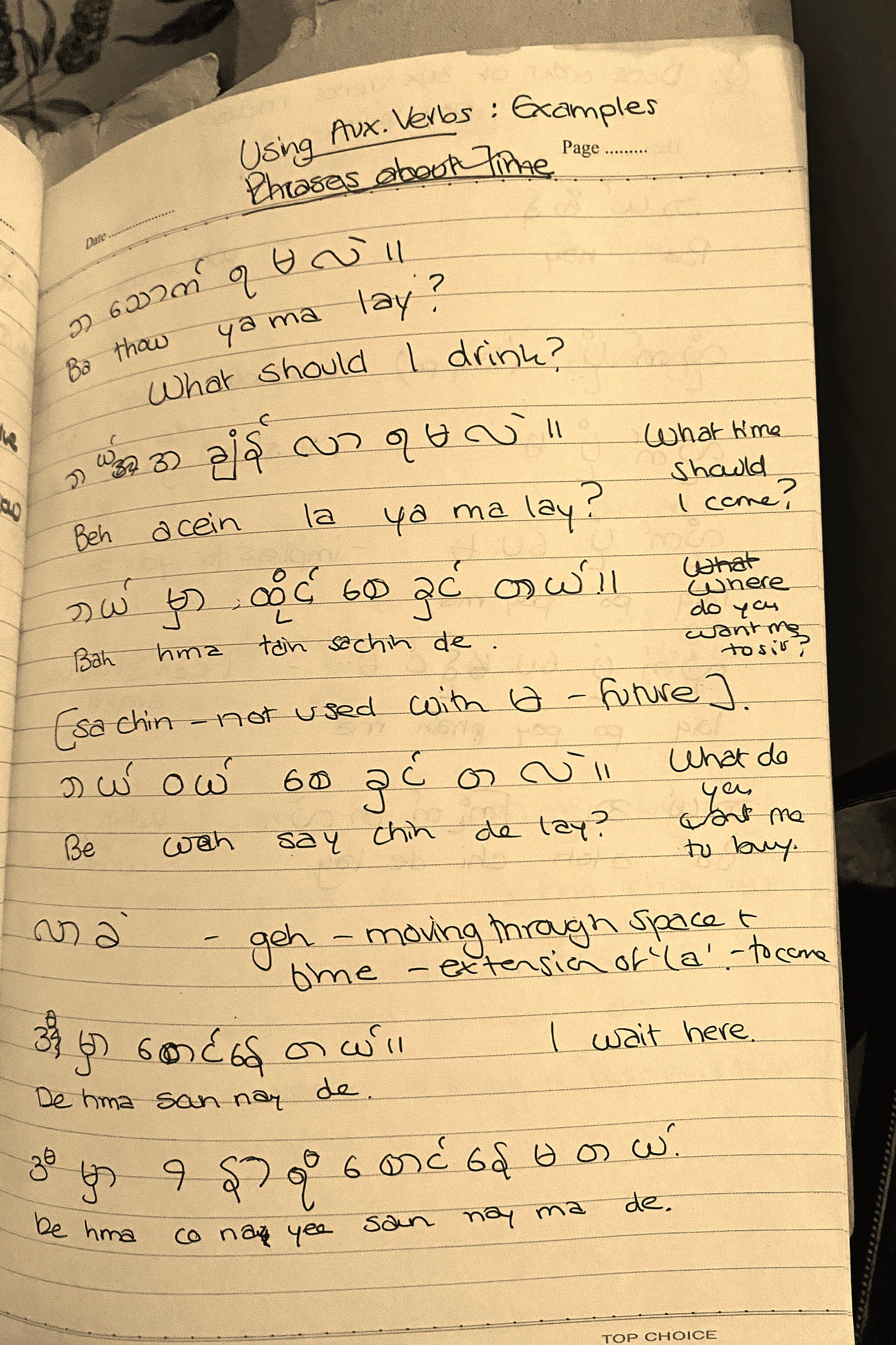

I learned Burmese because of my frustration with a taxi driver a few months after moving to Yangon. He took a wrong turn despite my protests, leaving us stuck in traffic for another 30 minutes, jammed between other cars on narrow streets. It could have been worse, and subconsciously, I realised that I was vulnerable without a way to talk to the people in this new home.

At the time, I wanted to keep studying Arabic, which seemed more ‘useful’ for my career. But my desire to talk to people in Yangon won over and quickly, without me realising, deleted all the Arabic in my brain.

It is a choice which reframed how I see language, how the world of sounds and words can work. The Burmese were the best people to learn with, excited by even my tiniest utterances. Eager to share their world.

Gaelic

When I look at all the languages I learned, I see my efforts to try to belong through verb tables, vocabulary cards and perfectly pronounced vowels.

I see bits of myself pulled into being. Like affirmations, languages cast spells, which you say over and over again until you become a bit like them.

I also know I have travelled the world and studied only colonisers’ languages. Words of victors and conquerors. The languages which have won.

Yet I didn’t feel like a conqueror - eagerly seeking out belonging everywhere I went. Even my native tongue is not truly mine.

Recently, I have been studying Scottish Gaelic. I am still not great at it.

I find it strange; a few generations back, my ancestors spoke in these words, but I am better at French.

I find Gaelic grammar validates ways of seeing and saying I already knew. Ways and words I was surrounded with, but didn’t know I could clasp onto.

And I wonder if meeting the world would have been different if I had been holding that knowing all along.

Friends,

Thank you for spending another week travelling with me.

I know some of you have your own language learning journeys, and I would love to know what they taught you.

Do you think our world would be different if we all were more connected to our Indigenous tongues and the insights they offer about the world?

Have different languages brought out a new side of your personality?

Have you forgotten any languages that you once knew how to speak?

Thank you for being here.

If you enjoy Notes from Saving the World and want to express your appreciation (which is welcome in all languages, including dance, song and coffee). Here are some ways you can say thank you:

Like this post.

Subscribe for weekly updates.

You can share this post.

You can fuel this newsletter (powered by oat flat whites).

If you liked this, you might also like:

If you want to know more about how I ended up travelling to all these places, you can find out more here:

I loved reading this Catriona, and I am inspired to write a similar post about my languages. Men criticizing a woman about how she speaks their language is something I have zero tolerance for...I was on the receiving end of that for too long (while the men in question failed to learn my language).

What a lovely post! I might steal this format (crediting you of course and linking to this post of yours). Languages are such a gift - they're like a doorway to a different world.