What the Charity Sector Taught Me About Success

The messy reality of progress helped me understand my family's own struggles

Hello friend,

I am a little late with this week’s letter. I do have a decent excuse, as in the past week I have travelled from Dubai to the Inner Hebrides of Scotland, then onto Glasgow and Edinburgh, catching stomach flu along the way, but also breathing in all the fresh air and wild countryside medicine of Scotland.

Returning home, I am reminded of TS Elliot’s words: “And the end of all our exploring/Will be to arrive where we started/And know the place for the first time.”

And as I reconnect with Scotland again, I wanted to rework a piece about that rediscovery of home, because after seeing the world from different vantage points, I find I see home with more complexity and compassion.

And, I will share next week’s inspiration challenges at the end of this post, if you are following on.

Gran and Grandpa had a big house on the outskirts of Dundee.

I didn’t know my Grandpa but I knew he won a scholarship to go to University, the first in his family, and because of this degree, he went ‘up in the world’, away from his Glasgow working-class household and onto the purchase of this house.

It is a classic story, the idea that we all have a shot at success, and in Presbyterian Scotland that shot comes through studies and hard work. It echoed my school history lessons about Glasgow’s development. Shipbuilding, colonial ventures, the enlightenment: hard work and intellect shaping physical evidence of progress.

So, without knowing him, I was taught by him, how to progress through life. I was taught to admire the big house with its elegant contents. I was to do well at school, go to university and let exam results shape a future my Grandpa had already made easier for me.

The problem was, I didn’t want to go up in the world. The idea of a superhighway to a stable nine-to-five horrified me. Instead, I found routes to escape the inevitable ‘career’: applying for ERASMUS study in France, a trainee role in Luxembourg, then a trainee charity job in Nicaragua, supporting myself, but not quite in the way that was expected.

Yet, when I arrived in Nicaragua at the age of twenty-four, despite not following this linear path, I seemed to expect Nicaragua would operate in straight lines.

I was frustrated not to see progress appearing before my eyes, as a result of the aid project I was working on. Instead, for the first time in my life, I saw the complicated way in which change takes place: not necessarily making things better, just making them different.

I could never reconcile my experiences in Nicaragua with those of my upbringing, until last year, when my Aunt told me more about the time the family moved to that big house. She was eight years old and her memory of ‘going up in the world’ was not positive: she found it a sad time.

She had left her old school, old friends and home in Glasgow. And moving into the big house, meant that daily life cost more money. My Gran went back to work to pay for the bills and the new furniture, which meant she couldn’t spend much time with my Aunt, who subsequently developed a strong resentment for the ‘nice’ furniture. My Aunt remembers other stresses at school and the efforts to keep up with this change, which left lasting marks on the family.

As a child, I saw only the grand house and the furniture. No one talked about the hidden losses and sorrows which lay hidden in the walls. No one mentioned that anything might have been lost by following the promises of progress.

School also didn’t teach me about the lost cultural practices which underwrote Glasgow’s growth.

No one talked about the ups and downs of living, no one mentioned the structural obstacles and the wounds needing healing. No one mentioned any of this.

My time in Nicaragua taught me something closer to my Aunt’s experience: that realistic change comes with disruption.

Progress requires that systems which operate one way, alter. That they adapt to a new way, which is deemed ‘better’, but really requires a choice.

And that choice asks us to devalue what we have in favour of the aspirations we are seeking.

It requires us to abandon old ways of living. To cast our values as backwards, old-fashioned or inessential: when really, they may have been important, essential and loved.

Walk With Me

What do you feel our society has asked you to devalue in the name of progress?

Do you have memories of change which required you to give up something you loved?

What do you wish your ancestors had held onto from previous times?

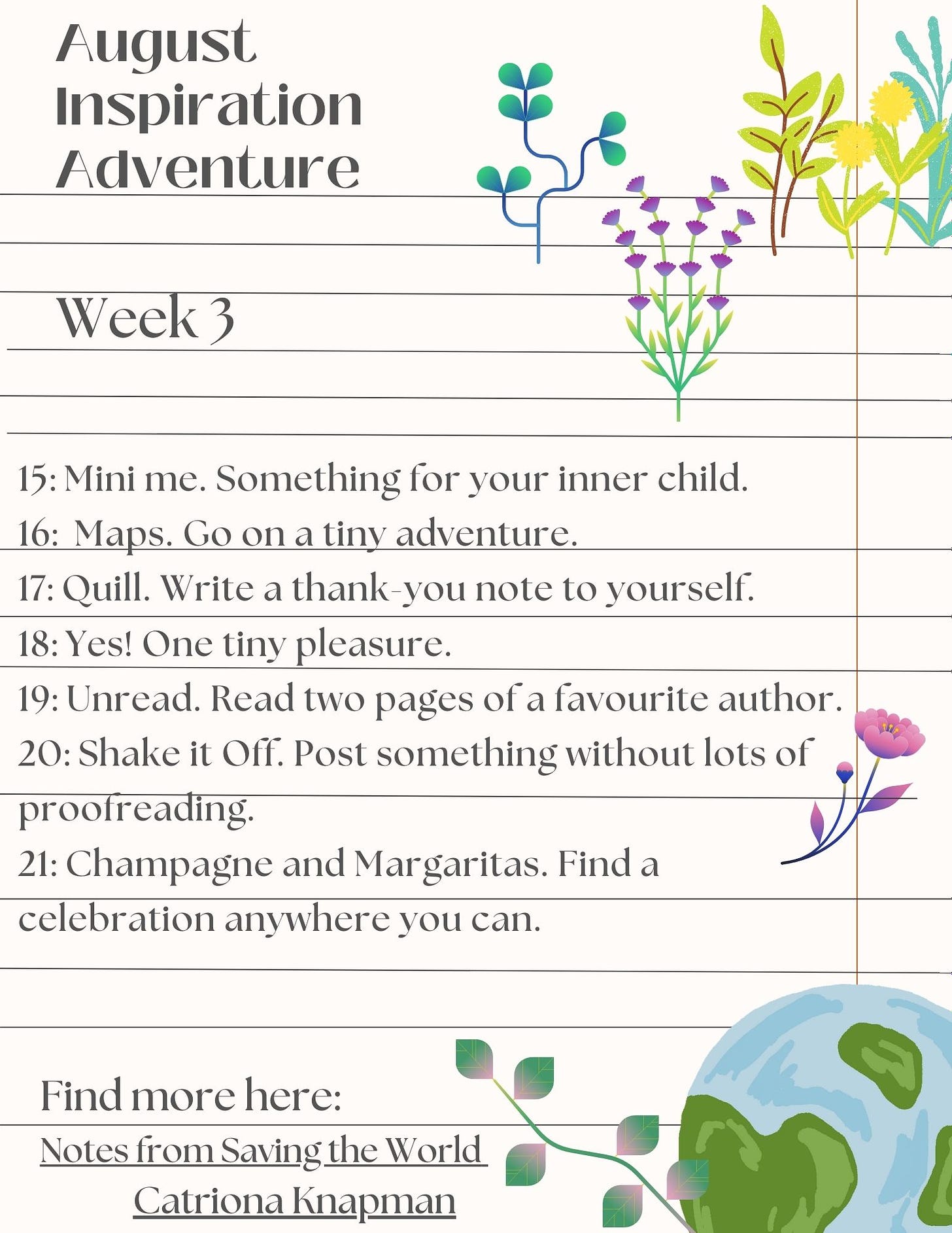

August Inspiration Adventure

How are you going seeking August inspiration?

I am overloaded with inspiration this week, from staring at the Scottish coastline after the 40-degree heat of Dubai’s desert.

Here are the prompts for the coming week:

Wow, I’m loving this way of looking at the world around us. We are often asked to disassociate ourselves from things or people to make it easier for us to accept what is being done to us. To accept this as some kind of progress, when really we have a lot more in common with those who come to share our community, than those who tell us we should turn against them instead. History as taught to us or read in books offers only one small viewpoint from which to look at the past. Even that which is handed down through family generations. I love how you gently weave the personal with the wider world and prompt us to take on that journey. I’ve typed and deleted and typed and deleted a lot here, but enough to know I have plenty to consider - both from your amazing daily August prompts and your questions. Thank you so much for this.

Thanks🙏